Japanoise, or Japanese noise refers to the noise scene in Japan. As the name suggests, noise is a music genre that explores the boundaries between “music” and “non-music”. Noise originated in Europa around 1910, influenced by futurism, surrealism and Fluxus. The instruments used vary widely. Noise features a fusion of traditional instruments and electronic sounds, recordings and machines. It sometimes is described as sound scape, for rhythm and structure are of minor importance.

Noise music is not easy to understand and it usually takes a long time before one starts to appreciate it. This is certainly the case in Japan, where harsh noise has still maintained its form of “pure noise”. Western noise music is often a fusion of noise and a different music style, like rock, pop or electronic music.

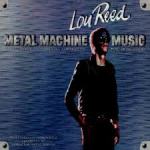

In the 1980s, noise rock (“commercial studio noise music”) used the unconventional noise heritage and mixed it with rock. The usual instrumentarium of guitars, drums, vocals and bass is in charge, but “noisy” elements like atonality and dissonance are incorporated as well. A famous noise rock album is Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music.

But then there is the question: is noise still music? The border between noise and music, especially in avant-gardist music styles, can be very vague.

there is no noise without the thought of noise – (…) noises come from specific places and specific conceptualisations. – Paul Hegarty: Full With Noise: Theory and Japanese Noise Music (2001)

In aesthetic terms, the category of ‘sound’ is often split in two: ‘noise’, which is chaotic, unfamiliar, and offensive; and ‘music’, which is harmonious, resonant, and divine. These opposing concepts are brought together in the phenomenon of Noise Music (…) – Joseph Klett and Alison Gerber: The Meaning of Indeterminacy: Noise Music as Performance (2014)

Like all modern arts, noise music serves another purpose: not (only) aesthetically appealing, but also conveying a certain meaning. With noise, fixed ideas about how music ought to sound like are questioned. The concepts of “music” and “noise” are highly subjective, if not closely linked with cultural and social expectations. As Attali points out: music is intimately tied up in the mode of production of a certain society. After all, noise music is not “likeable” or “fun” like commercial music is, and should therefore be approached in a different way.

Noise can be seen as structural: in the realm of law, of good citizenship, it is “undesired”, or “excessive” sound. In the realm of Law as that which operates rationality, noise is that which has always to be excluded – the exclusion having always already been and (not) gone, in order that the Law exists. This seems to indicate noise as a category, like the sublime, of domesticated exclusion. – id.

The noise scene in Japan is surprisingly strongly represented. It was introduced in the late 1970s, peaked in the 1980s and 1990s and is still alive and kicking today. Many major noise artists are Japanese, and musicians all over the world claim to be inspired by Japanoise and its subgenres and fusion genres. Notable Japanoise musicians or bands are Akita Masami (a.k.a. Merzbow), Hanatarash, Boredoms, Hijōkaidan, Incapacitants and Melt-Banana.

An important part of noise music is the performance. An artistic performance bears a decoded cultural meaning which provokes interaction with the audience. Klett and Gerber, however, state that performance in noise music is characterized by “indeterminacy”, and requires “an interactive listener”.

Notorious for its dangerous performances was the band Hanatarash. After cutting a dead cat in half with a knife, destroying a venue with a backhoe bulldozer, playing with circular saws and attempting to throw a molotov cocktail, they were eventually banned at most venues. Hanatarash brought the destructivism from their music on stage.

Noise is not a sweet music style (it is for example very difficult to make soft noise) and stands for chaos and dissonance. It is directly translated into musical violence, or even maybe physical pain, for it hurts the ears. Noise music does not fit in the usual concept of music, it can hardly be called music, because we culturally interpret the concept of “music” differently. In semiotics, noise conveys a meaning. It is often seen in a negative view, as a way of default communication. Since the 1970s, musicians brought noise into the paradigm of music, stimulating creativity and providing new insights on the topic of music and cultural sociology.

Facts for Fun

– Beautiful noise informs about the history of noise and its role in contemporary music.

– Looking for some unconventional music? Watch Sound of Noise, a Swedish movie about “musical terrorism”.

-Documentary People Who Do Noise

– I wrote a paper about Semiotics in Noise Music

Resources

– Hegarty, P. Full With Noise: Theory and Japanese Noise Music, 2001.

– Klett, J., and A. Gerber. “The Meaning of Indeterminacy: Noise Music as Performance.” Cultural Sociology 8, no. 3 (September 1, 2014): 275–90.

– Cassidy, Aaron, and Aaron Einbond, eds. Noise in and out as Music. Huddersfield: University of Huddersfield Press, 2013.

– Attali, Jacques. Noise: The Political Economy of Music. Theory and History of Literature, v. 16. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1985.

– Simpkins, Scott. Literary Semiotics: A Critical Approach. Lanham, Md: Lexington Books, 2001.

– Kahn, Douglas. Noise, Water, Meat a History of Sound in the Arts. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1999.

– Tofogu. Is This Noise Or Music? (It’s Noise), 2012.