Second and last part of our haenyŏ story focuses more generally on Korean women. Were they really dominated by men during Korean history?

PART 2 “IF A HEN CRIES, IT WILL BRING A HOUSE DOWN”

1.1 Powerful women

Traditionally, Korean women are regarded as powerless, dependent of man and submissive. This view, however, is the result of the last centuries, when a male-dominated structure was forced upon them. In early Chosŏn, women’s status was almost equal to that of men. Several indications for that theory can be found in genealogies (chokpo). Regardless of gender, all children and following generations of their descendants were written down. Adoption of boys for sonless families was rarely found and second marriages of women appeared to be socially accepted. The women’s share of inheritance was as large as that of their brothers’ and they carried the same responsibilities for ancestor worship. Women were relatively free in the choice of their marriage partner. In comparison with China, child brides were only reluctantly and at a later age given to the family of the bridegroom. Also, abuses of the child were harshly condemned.

Later on, powerful, independent and active women are also present, parallel to the Confucian structure. These women live outside usual forms of Korean society. There are those who make their own living, like shamans (mansin or mudang), professional women entertainers (kisaeng) or the haenyŏ of Jeju, as described above. It is also clear that housewives in the mountainous region of Korea are of equal standing as their husbands, except for those who can afford showing off public display of status. The division of gender, where men play an active, outside role in the public domain, and women a passive, inside role in the domestic domain, is allocated to households with enough property and prestige to assure the “invisibility” of their female members. Those invisible wives, nevertheless, disposed of power in their own domain. They projected their influence on husband and children. Men in the villages often dealt merely with ritualistic issues, rendering their wives public power.

The duality of these female figures was that they were at the same time denigrated and indispensable. They proved that power could not be completely taken away from women, as the Neo-Confucian system attempted.

1.2 A male-dominated society

Confucianism takes the family as the central pillar of society. Up till now, “the five relationships”, whereof those between parent and child, and between husband and wife concerned the family structure, influenced Korean values to a high degree. Especially the relationship between father and son was emphasized. More than a relationship based on love between spouses, filial piety lies as a key virtue on the base of a peaceful society. In all relationships, the man came hierarchically first. These values were given stimulus during late Chosŏn, where Neo-Confucianism became established a state ideology. The ideal of male superiority in patrilineal lineage was forced upon the family structure, and the rule of “three obediences” (daughters to their fathers, wives to their husbands and mothers to their sons in later years) had to be respected. Women, as determined three times submissive, should completely sacrifice themselves to serve the other, male members of the family. She was supposed to keep silent and do as she was told. The proverb 암탉이 울면 집안이 망한다 (amtagi ulmyŏn jibani manghanda), translated as “If the hen cries, it will bring a house down” or “It is a sad house when the hen crows louder than the cock”, demonstrates women’s position at those times. Another method to rule over women was the “seven vices” (disobedience to parents-in-law, failing to bear a son, adultery, jealousy, contracting a harmful disease, malicious gossip and theft), valid reasons for men to eject their wives. Obviously, women did not have the right to request a divorce or to choose their spouse themselves. Inheritance shares were much smaller or not allotted, despite the law on equal distribution of properties among descendants.

Grabbing the girl’s wrist: exposure of a male dominated society in Korean drama. Credits and interesting article on http://outsideseoul.blogspot.be/2012/08/the-other-f-word-feminism-versus-korean.html

As Neo-Confucianism was established as the state ideology, discrimination of women by unequal relationships was justified by law. However, the law also prescribed children to respect both their parents. Against the seven vices, there were three reasons for remaining married.

As in China, Confucianism was the philosophy that influenced Korean society most. Buddhism, in contrast, has never had an equally nationwide influence on family structure, as it appealed primarily to the higher class.

1.3 Towards gender equality

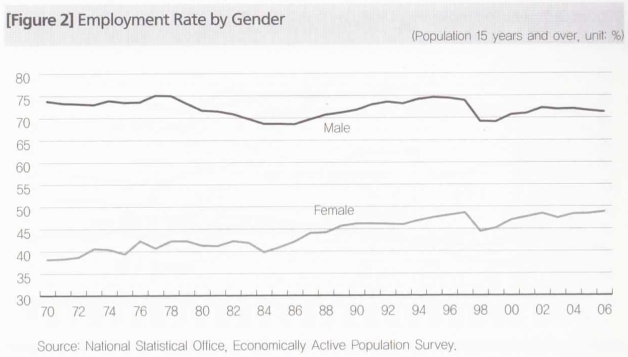

Despite rapid economic development and urbanization, the social, political or legal status of women in 1960 did not improve. Sons were given priority in food, clothing and education. Thirty years later, the concept of male superiority was still present. Entering the labor market did not evidently erase male-dominated structures, as could be observed in differences between pay, position and promotion. Even now, women are urged to resign by telling them “they would better get married soon.” After the marriage, women are expected to become housewives.

Korean employment rate 1970 – 2006. Credits and site about korean feminism: http://www.thegrandnarrative.com

The last twenty years, major changes improved gender relations to a high extent.Cohabitation before marriage has become more common, women charging their husband for divorce socially accepted and son preference has dropped. The male-dominated family structure has shifted towards a husband-wife type. While household tasks were mainly performed by women, young men nowadays are more willing to do chores at home. There is a large difference in values between the older and younger generation: Korean youths appear to be most reluctant in accepting and performing Confucian values among adolescents in 17 Asia-Pacific countries.

CONCLUSION: “THREE WOMEN MAKE A MARKET”

This proverb 여자 셋 이 모이면 접시가 깨진다 (yŏja set shi mo i myŏn jŏpsiga kkae jinda) is used to describe women as talkative, but I would like to use it for describing the situation of women on Jeju. It is suitable in the literal meaning, for these women actually provided a market system on the island. In the figurative meaning, it is the other way around. The men at home were regarded as the talkative ones, chatting and gossiping their weariness away with other “house men”. If not at sea, they had to look after the children and do household chores. Although the women of Jeju held economic power and enjoyed higher standing than the average Korean woman, their social status was always inferior to men’s. Consequently, the effects of the matriarchal family structure on Jeju did not change their marginal position socially or politically.

When we apply the proverb to women on the Korean mainland, it becomes clear that the Confucian ideal of powerless women is an illusion. Women did not keep silent all the time, but influenced their surroundings in their own way. They were powerful in the domestic domain, a place where men were not allowed and could not interfere. The image of the traditional Korean women is also produced in late Chosŏn, as before that time, women were regarded as almost equally to men.

The purpose of this paper was to show that the black-and-white representations of Korean women should be adjusted. Haenyŏ did not rule over men, and housewives were not as powerless as they seemed. Their hierarchical position, however, has always been lower than that of men. During history, this position was heavily reinforced by Confucianism. The legacy of this ideology still remains present today in the Korean family structure.

Gender equality in Korean ads? Again from http://www.thegrandnarrative.com

References

– Choi, Jung-wha, and Hyang-Ok Lim. This Is Korea: All You Ever Wanted to Know About Korea. Seoul, Korea: Hollym, 2010.

– Kim, Kyong-dong, and Korea Herald. Social Change in Korea. Paju-si: Jimoondang, 2008.

– Nemeth, David J. The Architecture of Ideology: Neo-confucian Imprinting on Cheju Island, Korea. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

– Gwon, Gwi Sook. “Changing Labor Processes of Women’s Work: The Haenyo of Jeju Island.” Korean Studies, Vol. 29 (2005): 114-136.

– Dawnhee, Yim Janellis. “Korean Women: View from the Inner Room. by Laurel Kendall; Mark Peterson: Review.” The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 44, No. 4 (Aug., 1985), 850-852.

– Lewis, Linda S. “View from the Inner Room. by Laurel Kendall; Mark Peterson: Review.” Signs, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Spring, 1987), 582-586.

– Jai, Poong Ryu. “Korean Women: View From the Inner Room. by Laurel Kendall; Mark Peterson: Review.” Pacific Affairs, Vol. 59, No. 2 (Summer, 1986), 335-337.

– Park, Insook Han; Cho, Lee-Jay. “Confucianism and the Korean Family.”Journal of Comparative Family Studies, Vol. 26, No. 1.

– “Haeneyo: The Last Generations of Korean Mermaids.” Grrrl Traveler, n.d. http://grrrltraveler.com/sightseeing/jejus-haeneyo/.

– “Lady Good Divers | Artinfo.” Artinfo, n.d. http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/28043/lady-good-divers.

The Island of Jeju is situated in the Korea Strait, southwest of mainland Korea. Its economy has traditionally been dominated by the fishing industry, until recently when tourism began to play an important role. Because of the isolated location, the influence from outside and the occupation by Japan, language and culture evolved in their own way. One of the most striking differences is the existence of a matriarchal family structure in the past.

The Island of Jeju is situated in the Korea Strait, southwest of mainland Korea. Its economy has traditionally been dominated by the fishing industry, until recently when tourism began to play an important role. Because of the isolated location, the influence from outside and the occupation by Japan, language and culture evolved in their own way. One of the most striking differences is the existence of a matriarchal family structure in the past.